There's Something "a miss" in Wondo's Legacy

/by @jmoorequakes

Christopher Wondolowski should be an American sports icon. He should be beloved and admired. If he is hated by anyone, it should be by MLS fans in the same way Indianapolis Colts fans “hate” Tom Brady. He is the underdog of underdogs – the working class man who beats the talented elite at their own game. At 36, he keeps breaking scoring records in MLS, including setting the all-time big one a few weeks ago with a four-goal match. He is on the precipice of being the first player to score 10+ goals in 10 straight MLS seasons. His time and opportunity with the US Men’s National Team should have been longer than it was – but for many fans, there would be no cry for Wondolowski’s return to the national team. No matter how many goals he scored or how often his league form was more impressive than the strikers getting the call, his national team legacy was cemented. Outside of a few San Jose Earthquakes fans and pundits, there are no calls for “Wondo” to be on the team by the American soccer public because of one infamous situation that occurred on July 1, 2014.

Today marks the fifth anniversary of that day. Chris Wondolowski will do what he does on any Monday following a Saturday MLS game. He will begin the process of preparing for the next game. Even though the Earthquakes soundly defeated the LA Galaxy in front of 50,850 at Stanford Stadium on Saturday, it is already in the past, and he’s already looking forward to the next one. Dwelling in the past would have crushed him long ago. For every goal, there are two or three misses. If you focus on the misses, Wondo, like most excellent goalscorers would probably tell you that you will never make the next one.

Only for Wondo it’s highly unlikely there will ever be a “next one” for the USMNT. If the toxicity on Twitter is any indication whenever he breaks a record, he would have to win a Men’s World Cup to erase the Belgium game – and probably still half the tweets would say, “yeah, but he missed that sitter against Belgium”, complete with a gif of the shot using an angle diagonally behind the goal. Even when he broke Landon Donovan’s all-time mark this season, at least two-thirds of the comments on any tweet from MLS, Alexi Lalas, Grant Wahl, and the like, were about the Belgium miss.

Before we move forward, let me share my own personal Wondo story. In 2012, my seven-year-old son was getting into competitive soccer. I decided he needed more exposure to the game than Fox Soccer was providing at the time, so I started taking him to Earthquakes games to see live matches. We went to an Earthquakes friendly with Swansea City at Santa Clara University, and he brought a program and a sharpie. We didn’t know at the time where the best spots were for autographs, and found ourselves standing by ourselves away from where the autographs were being signed. After the game was done and hands were shaken, Chris looked around from standing in the middle of the pitch and saw my son standing all alone against the railing. Wondo immediately ran over, jumped over the advertising boards, and gave him an autograph. That’s Wondo for you – never missing an opportunity to positively impact a young player. In 2014, he signed my son’s US jersey in the final Earthquakes game before going to the World Cup. My son was wearing that jersey during the game on July 1, 2014.

I understand that being nice to my son and other soccer loving youths in the Bay Area isn’t likely going to absolve Wondolowski of that fateful miss against Belgium in the 2014 World Cup. If you still harbor ill will toward him for that day, then this article is unlikely to change your mind. After all, this Grantland article still exists which captures the painful emotions of a nation, a national team, and Wondo himself better than any article I could possibly write. However, this is an attempt to bring an analytical approach to a matter of the heart.

Years ago one of my favorite sports segments on Fox Sports and ESPN (depending on the year) was SportsScience. The aim of the show was to take an incredible sports moment and break it down with physics – the speed of a player, the spin of a ball – and show the slimmest of margins for how the moment happened. The show demonstrated regularly the greatest of accomplishments would not have happened if they were off by tenths of a second here or there. I wish SportsScience was still around to analyze this situation, because I strongly believe the physics at play here would have much more to do with the outcome than data analytics could possibly show. But, alas, I had a poor Physics teacher in high school, and got my only C between grades 1 and 12 in that class. As such, I am woefully unable to do anything resembling a proper physics breakdown (if you can, my DMs are open). Instead, I will use data to analyze the shot and the play leading up to it and compare it to similar situations.

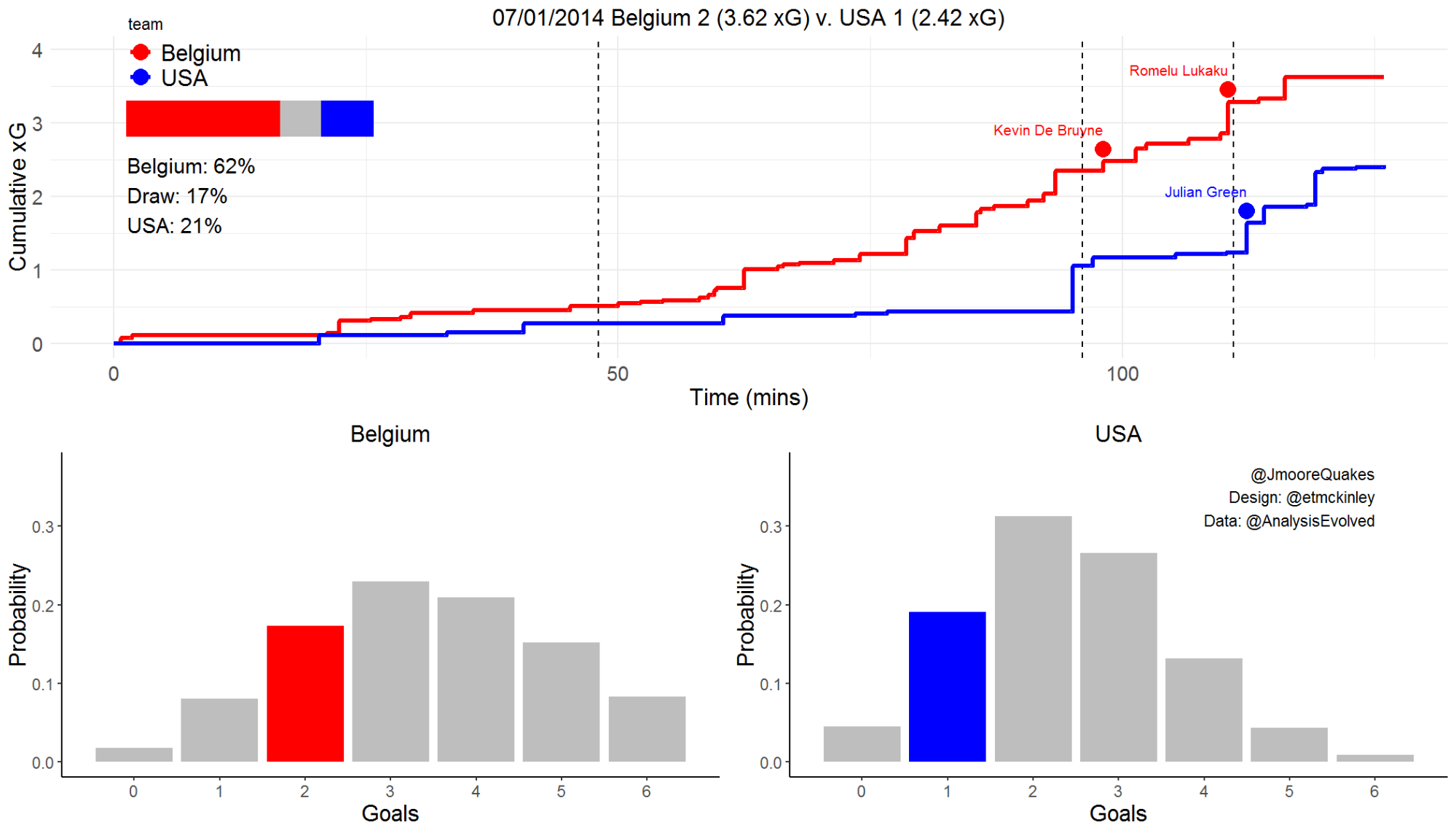

Let’s start by looking at the expected goal (xG) probabilities. xG probabilities tell us the likelihood that a team will score a goal based on the quality of the shot. With xG probabilities, effectively three 0.2 xG (20% chance) shots are worth the same as one 0.6 (60% chance) xG shot. We’ll revisit this later.

Taking away Wondolowski’s miss, which was the final shot of regulation, using xG probabilities, the US had a 4% chance of winning the game in regulation time. It’s impossible to say what would have happened beyond that point without Wondo, but with these numbers it doesn’t look good. The match only had a 13% chance of going to extra time. Chalk it up to the biggest game of Tim Howard’s life or less-than-stellar shooting by the Belgians, but even without “The Miss” the Americans were extremely unlikely to win this game.

Once Wondolowski takes the final shot of regulation, the xG probabilities have now shifted to a mere 9% for a US win. While it seems simple to say “if Wondo makes that shot, the US beats Belgium”, the fact is that if these two teams played this match another 10 times in the same way, the US might not win any of them.

As much as it pains most of us to see this again, let’s review the match video leading up to the final shot. Instead of just focusing on the final shot, we’ll examine the entire possession.

Let’s start by acknowledging there was no offside on the play. One of the frequent comments in Wondolowski’s defense is, “well, the AR called offside anyway, so it wouldn’t have counted.” American TV play-by-play commentator Ian Darke (not heard on this particular video) was either confused or, perhaps sensing the moment, was protecting him. Other angles have shown the AR was merely pointing for a goal kick.

A rant: Conversely, color commentator Taylor Twellman did Wondolowski no favors with his incessant harping on the miss both during the game and in the weeks to come. Had Twellman spent the same time on the failures of other attackers in the match or examining why the defense gave up 38 shots and 26 shots on goal, the public perception might have been somewhat different. If the Americans had finished their high quality chances Wondolowski provided in extra time, the match would have likely come down to penalty kicks with a chance for Wondolowski, a quality penalty taker, to redeem himself. But Twellman gave it no commentary then or afterward. Instead, US goalkeeper Tim Howard is a hero, Wondolowski is the goat (instead of the GOAT), and Dempsey and the defense escaped any blame. The scrutiny Klinsmann faced was more about selecting Wondolowski over Landon Donovan for the squad. Howard would go on to sign one of the biggest MLS contracts ever following this game, and arguably has never performed in MLS as he did in that match. Now that I’ve gotten that off my chest, let’s move forward.

Wondolowski’s work rate here cannot be denied. First, he wins an aerial duel that gives the ball to Clint Dempsey in a dangerous spot with attacking options. Dempsey can give the ball to arguably the best US distributor, Michael Bradley, or even switch the point of attack, but instead he tries to play a ball over Wondolowski. It’s a really poor effort. Dempsey plays the ball in just about the only place Wondo cannot win it and create a shot. Instead of giving up on the play, Wondolowski goes hard after the ball, sacrifices his body, and forces the defender to clear it out to the sideline. Then, in a heads-up play that catches the Belgium defense resting, Wondolowski knows he can’t be offside for the throw-in, runs from inside the 18, and wins the ball deep in a potentially dangerous crossing area. The cross attempt is blocked up into the air 15 yards away. Wondo gets tripped up after the cross attempt and yet still wins another aerial duel he should not have won while five other USMNT players in the frame stand around and watch him. The US retains possession, play the ball wide to Yedlin, who, under no pressure, plays a cross that no US player can possibly win. The ball is cleared out around 35 yards from goal, and now the infamous sequence takes place: first, Michael Bradley takes the clearance off his chest and hits a ball about 30 feet high and into the box. Next, Jermaine Jones heads it from about two yards left of the penalty dot about 10 feet into the air and into the path of Wondolowski. Thibaut Courtois – at 6’ 6” and 200+ pounds – being one of the best keepers in the world that year, is jumping feet first toward Wondolowski in a way to take away the near post and center of the goal simultaneously. Wondolowski takes it on the short hop and puts it over the onrushing Belgian goalkeeper and over the goal. The camera immediately shows a horrified Jürgen Klinsmann and two US players rushing forward. With an xG of 0.63 (63% chance), this was clearly the most dangerous US opportunity of the game. Since Tim Howard had made 11 saves, the chance to win the game had still been there. And, yet, it never really was…

In extra time, the US will go on to have their best chances of the match, but Howard’s magic starts to fall apart, as does what’s left of the USMNT defense, while Belgium scores two quality goals in the first extra time period. But the game is far from over, and early in the second extra time period Julian Green makes an inside run from the left wing and effectively mishits a volley from a perfect chipped ball from Michael Bradley. The mishit off of Green’s toe momentarily freezes Courtois and the ball finds the right corner of the net. The US are now only down 2-1 with enough time remaining. It’s at this point the USMNT play their best soccer of the match, firing off six shots over the final 12 minutes while controlling much of the possession. The two best chances, shots from Jermaine Jones and Clint Dempsey, will come from Wondolowski passes. From the angle shown by the camera, it temporarily appears Jones’ shot will tie it up, but then it harmlessly goes wide – it’s a quality 0.22 xG chance, but it won’t be the best chance.

The best real chance of the match for the US will come with seven minutes left in extra time in what is clearly a designed set piece play about 33 yards from goal. With Jones and Bradley standing over the ball, Wondolowski runs around the cluster of players for a simple pass in front of the 18. With seven Belgian players in the vicinity, Wondo redirects a one-touch pass to Dempsey with his weaker left foot, perfectly splitting the defenders. It’s the only available option, and Wondo finds it in tenths of a second. The pass had to be firm and gets a little under Dempsey, who more stumbles into a shot than hits it. It comes off more like a bad touch, and Dempsey immediately tries to follow it up. Courtois makes no error here. Like he did with Wondo’s shot, he closes down the near post and central area for a potential Dempsey follow up attempt quickly and slides in to deflect the ball back to the middle of the penalty box. In the initial camera angle, it appears Wondolowski has a split second to react and shoot the rebound and doesn’t. However, another angle behind the goal reveals it was actually Julian Green who is the closest, but he’s tied up with a Belgium player and can’t get off a clean rebound shot. This chance from Dempsey has an 0.52 xG, a 50/50 chance, and a mere 0.11 xG lower than Wondo’s miss of 0.63 xG. The cameras don’t show the reaction from Klinsmann or the bench players. This is the power of television at its best (or worst) to persuade thoughts and cement memories.

Here are the final xG probabilities.

Despite giving up two goals in extra time, the US generated enough opportunities to increase their probability of winning ahead of penalties from 9% to 21%.

So, case closed, right? Wondoloski’s miss was a big xG value, and while Dempsey could have done better, perhaps Wondo’s pass wasn’t perfect enough. As soccer analysts, we spend a lot of time talking about expected goals, but the model here has many unsupplied factors. In aggregate, these factors, or flaws in the model, if you will, are not big – in fact, over 10 games or so into a season, the model is incredibly accurate. However, at an individual shot level, the model is missing some key information that is not available to us to be able to say emphatically a particular shot chance is correct. If you are a regular reader of Harrison Crow’s Lowered Expectations columns on American Soccer Analysis, you know that there are 0.50+ xG shots every week that really have no chance of going in once you view the circumstances around them. Pass direction and height, body positioning, defender positioning, keeper positioning, physics, and more factors not reflected in the xG model in reality have huge implications on shots. xG merely represents an average of all those factors over thousands of similar shots over many years from open play, free kicks, corners, and more.

In addition to the physics of a spinning ball coming off the turf on an in-between hop, there are important factors to consider about this shot: the first is the size and positioning of Thibaut Courtois, and the second is the pass is coming in from a header that goes about 10 feet high at its apex, effectively across Wondolowski’s body, and almost over his left shoulder. It’s the equivalent of an over the shoulder catch if someone was catching and throwing to hit a target perfectly in a single motion.

photo courtesy of mlssoccer.com

Keeper Positioning

Courtois’ position is just about as good as it can be. He makes himself as big as possible and closes down the angles quickly. The best case scenario here for Wondolowski is a ball on the ground, anywhere really. Other angles showed a ball to the far post or even a redirect to Dempsey were potential options. The issue with hitting a ball bouncing off the ground is that Wondolowski is arriving late to the ball location, and given Courtois’ closing speed, the only way to get a shot is to get his foot ahead of his body. This, as any youth competitive coach can tell you, creates a physics problem where balls pretty much only go up off of any foot.

Passing Angle

The key pass here is coming from Jermaine Jones about two yards left of the penalty dot. The ball comes to Jones from a long ball hit about 30 feet into the air by Bradley. Jones’ header is about 10 feet high over Wondolowski’s left shoulder and is immediately shot from the same spot as it is received. In order to gauge if this shot is a 63% “sitter” as the xG says it may be, we need to search the ASA data set for similar passes that led to shots. As it turns out, this is a very uncommon pass. Looking for headed key passes within three yards any direction from Jones’ location in open play, we come up with eight passes since 2013 which fit this criteria.

| Date | Half | Time | Team | Opponent | Passer | Recipient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3/3/13 | 2 | 54:46:00 | Portland | NYRB | Mikael Silvestre | Andrew Jean-Baptiste |

| 3/23/13 | 1 | 32:49:00 | San Jose | Seattle | Ramiro Corrales | Ty Harden |

| 6/1/13 | 2 | 78:39:00 | Philadelphia | Toronto | Conor Casey | Jack McInerney |

| 5/24/14 | 1 | 14:57 | Real Salt Lake | FC Dallas | Nat Borchers | Ned Grabavoy |

| 9/12/14 | 1 | 19:43 | Seattle | Real Salt Lake | Chad Marshall | Obafemi Martins |

| 6/27/15 | 2 | 92:55:00 | L.A. Galaxy | San Jose | Alan Gordon | Robbie Keane |

| 3/5/17 | 2 | 49:56:00 | NYRB | Atlanta United | Bradley Wright-Phillips | Aaron Long |

| 4/14/17 | 2 | 94:01:00 | Seattle | Vancouver | Henry Wingo | Clint Dempsey |

Now the next step is to review their resulting shots.

| Date | Time | Half | Team | Shooter | Keeper | Passer | xG | Body Part | Result | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3/3/13 | 54:48:00 | 2 | Portland | Andrew Jean-Baptiste | Luis Robles | Mikael Silvestre | 0.37 | Right foot | Blocked | 9.2 |

| 3/23/13 | 32:50:00 | 1 | San Jose | Ty Harden | Michael Gspurning | Ramiro Corrales | 0.2 | Left foot | Blocked | 13.1 |

| 6/1/13 | 78:40:00 | 2 | Philadelphia | Jack McInerney | Joe Bendik | Conor Casey | 0.3 | Right foot | Saved | 10.5 |

| 5/24/14 | 14:59 | 1 | Real Salt Lake | Ned Grabavoy | Chris Seitz | Nat Borchers | 0.08 | Head | Miss | 11.4 |

| 9/12/14 | 19:44 | 1 | Seattle | Obafemi Martins | Nick Rimando | Chad Marshall | 0.34 | Left foot | Post | 9.7 |

| 6/27/15 | 92:57:00 | 2 | L.A. Galaxy | Robbie Keane | David Bingham | Alan Gordon | 0.18 | Right foot | Blocked | 13.4 |

| 3/5/17 | 49:57:00 | 2 | New York | Aaron Long | Alec Kann | Bradley Wright-Phillips | 0.18 | Right foot | Saved | 12.7 |

| 4/14/17 | 94:02:00 | 2 | Seattle | Clint Dempsey | David Ousted | Henry Wingo | 0.42 | Right foot | Saved | 8.3 |

None of the shots were made.

There are three of these potentially similar shots that catch my eye: Obafemi Martins in 2014, Robbie Keane in 2015, and Clint Dempsey (!) in 2017. Let’s take a look at Martins:

That didn’t go well. Let’s see Keano’s:

This looks a bit more like what we want, but there are defenders on top of him. What I’m really interested in is Dempsey’s shot.

Not at all the same, but an exciting finish to a game nonetheless. Clearly a major factor here is pass height which is not something we have in the ASA data set. If the passes are headed into the ground, the opportunity is far simpler, otherwise it’s very difficult.

One thing we could do to find more shots is to flip the pitch for passes going from right-to-left instead of left-to-right. We could take passes from the right of the penalty dot to the left side of the goal. Here we find eight more passes:

| Date | Time | Half | Team | Shooter | Keeper | Passer | xG | Body Part | Result | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8/10/13 | 68:59:00 | 2 | San Jose | Sam Cronin | David Ousted | Alan Gordon | 0.387866127 | Left foot | Blocked | 8.85 |

| 8/10/13 | 34:31:00 | 1 | Philadelphia | Conor Casey | Bill Hamid | Sebastien Le Toux | 0.259415915 | Right foot | Goal | 11.18 |

| 6/7/14 | 75:42:00 | 2 | San Jose | Billy Schuler | Joe Bendik | Steven Lenhart | 0.296012557 | Right foot | Blocked | 10.41 |

| 6/27/15 | 28:49:00 | 1 | Salt Lake | Olmes Garcia | Steve Clark | Phanuel Kavita | 0.316325423 | Right foot | Miss | 7.73 |

| 10/25/15 | 1:20 | 1 | Portland | Fanendo Adi | Zac MacMath | Liam Ridgewell | 0.097509356 | Head | Saved | 12.78 |

| 5/7/16 | 84:19:00 | 2 | Vancouver | Octavio Rivero | Jake Gleeson | Kendall Waston | 0.138151221 | Head | Saved | 12.06 |

| 9/30/17 | 61:42:00 | 2 | New England | Juan Agudelo | Brad Guzan | Antonio Mlinar Delamea | 0.117204506 | Head | Saved | 11.51 |

| 3/30/19 | 51:14:00 | 2 | Seattle | Raul Ruidiaz | Maxime Crepeau | Cristian Roldan | 0.12985418 | Left foot | Blocked | 11.91 |

One of these opportunities turns into a goal – just one.

The only goal comes from current Colorado Rapids interim coach Conor Casey which he scored against DC United, assisted by Sebastien Le Toux, on a 0.25 xG shot in 2013.

The headed ball to the ground is easier to handle and results in a goal, finally. Only one of the 18 similar pass/shot combinations (6.25%) in the data set ended in a goal.

“Ah, but that’s MLS,” you say. “The World Cup has much better quality.” Sure, let’s go with that. Fortunately, I was able to obtain all the passes and shots in the Big 5 European Leagues from 2009 to 2019 – that’s the closest we will get to “World Cup quality” with any good sized data volume. Using the same parameters as MLS, there were only eight headed passes from within three yards of Jones correlated to shots within three yards of Wondo…and no goals at all.

Between the two data sets, that’s one goal out of 24 shots – a 4.2% chance, including situations where the ball was headed directly to the feet of the player. While we certainly don’t have a large enough sample size to make a definitive claim on the percent chance the Wondolowski miss really was, given the potential range is somewhere between 4.2% and 63%, and given it is clearly not a common, practiced situation, it cannot be called a “sitter” or a “tap in”. And the Dempsey miss? The MLS data set had 10 passes and 3 goals – a 30% conversion rate. The sample sizes are really small, but the additional circumstances around both shots seem to yield a potentially lower probability than xG indicates. Given this, the chance for a US victory against Belgium was likely far lower than even the xG probabilities indicated.

Conclusion

Very few shots are true “gimmes”, and xG has its flaws even in 2019, especially with individual shots. The emotions of soccer can get us carried away sometimes, but proper analysis can help ground our perspective if we are willing to listen. In the 2014 World Cup against Belgium, Chris Wondolowski created higher expected goals chances in total probability (0.74) than the one shot he missed (0.63), however he will forever be remembered not for scrappy play and chance creation, but for The Miss. By looking at more characteristics around a situation we can better determine the chance of a goal for a particular shot than general-purpose xG models, intended to provide a picture over several games, can indicate. After digging deeper into the Wondolowski miss vs. Belgium five years ago, we can now say: “No, Landon Donovan probably wouldn’t have put that one away.”