In Defense of the San Jose Earthquakes and American Soccer

/Note: This is part II of the post using a finishing rate model and the binomial distribution to analyze game outcomes. Here is part I. As if American soccer fans weren’t beaten down enough with the removal of 3 MLS clubs from the CONCACAF Champions League, Toluca coach Jose Cardozo questioned the growth of American soccer and criticized the strategy the San Jose Earthquake employed during Toluca’s penalty-kick win last Wednesday. Mark Watson’s team clearly packed it in defensively and looked to play “1,000 long balls” on the counterattack. It certainly doesn’t make for beautiful fluid soccer but was it a smart strategy? Are the Earthquakes really worthy of the criticism?

Perhaps it’s fitting that Toluca is almost 10,000 feet above sea level because at that level the strategy did look like a disaster. Toluca controlled the ball for 71.8% of the match and ripped off 36 shots to the Earthquakes' 10. It does appear that San Jose was indeed lucky to be sitting 1-1 at the end of match. The fact that Toluca only scored one lone goal in those 36 shots must have been either unlucky or great defense, right? Or could it possibly have been expected?

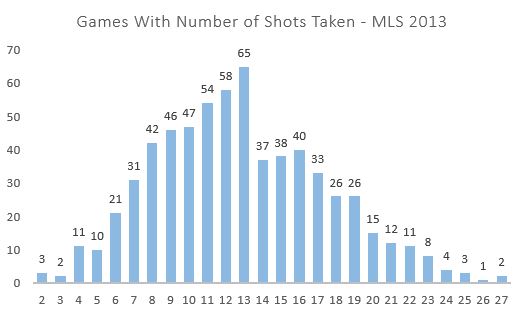

The prior post examined using the binomial distribution to predict goals scored, and again one of the takeaways was that the finishing rates and expected goals scored in a match decline as shots increase, as seen below. This is a function of "defensive density," I’ll call it, or basically how many players a team is committing to defense. When more players are committed to defending, the offense has the ball more and ultimately takes more shots. But due to the defensive intensity, the offense is less likely to score on each shot.

Mapping that curve to an expected goals chart you can see that the Earthquakes expected goals are not that different from Toluca’s despite the extreme shot differential.

Given this shot distribution, let’s apply the binomial distribution model to determine what the probability was of San Jose advancing to the semifinals of the Champions League. I’m going to use the actual shots and the expected finishing rate to model the outcomes. The actual shots taken can be controlled through Mark Watson’s strategy, but it's best to use expected finishing rates to simulate what outcomes the Earthquakes were striving for. Going into the match the Earthquake needed a 1-1 draw to force a shootout. Any better result would have seen them advancing and anything worse would have seen them eliminated.

Inputs:

Toluca Shots: 36

Toluca Expected Finishing Rate: 3.6%

San Jose Shots: 10

San Jose Expected Finishing Rate: 11.2%

Outcomes:

Toluca Win: 39.6%

Toluca 0-0 Draw: 8.3%

Toluca 1-1 Draw: 13.9% x 50% PK Toluca = 6.9%

Total Probability Toluca advances= 54.9%

San Jose Win: 32.3%

2-2 or higher Draw = 5.8%

San Jose 1-1 Draw: 13.9% x 50% PK San Jose = 6.9%

Total Probability San Jose Advances = 45.1%

The odds of San Jose advancing with that strategy are clearly not as bad as the 10,000-foot level might indicate. Counterattacking soccer certainly isn’t pretty, but it wouldn’t still exist if it weren’t considered a solid strategy.

It’s difficult, but we can also try to simulate what a “normal” possession-based strategy might have looked like in Toluca. In MLS the average possession for the home team this year is 52.5% netting 15.1 shots per game. In Liga MX play, Toluca is only averaging about 11.4 shots per game so they are not a prolific shooting team. They are finishing at an excellent 15.2%, which could be the reason San Jose attempted to pack it in defensively. The away team in MLS is averaging 10.4 shots per game. If we assume that a more possession oriented strategy would have resulted in a typical MLS game then we have the following expected goals outcomes.

Notice the expected goal differential is actually worse for San Jose by .05 goals. Though it may not be statistically significant, at the very least we can say that San Jose's strategy was not ridiculous.

Re-running the expected outcomes with the above scenario reveals that San Jose advances 43.3% of the time. A 1.8% increase in the probability of advancing did not deserve any criticism, and definitely not such harsh criticism. It shows that the Earthquakes probably weren’t wrong in their approach to the match. And if we had factored in a higher finishing rate for Toluca, the probabilities would favor the counterattack strategy even more.

Even though the US struck out again in the CONCACAF Champions League, American's don't need to take abuse for their style of play. After all, soccer is about winning, and in the case of a tie, advancing. We shouldn't be ashamed or be criticized when we do whatever it takes to move on.